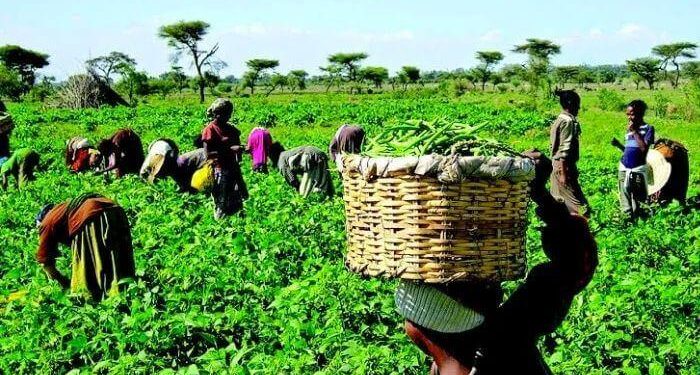

Nigerian farmers have voiced concerns over the Federal Government’s dry season farming initiatives, questioning their inclusivity and implementation. While the government has promised interventions to address food insecurity through irrigation and mechanized farming, many farmers argue that these efforts are selective and inadequate.

The Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security has highlighted plans to shift Nigeria’s agriculture from rainfed to year-round farming. Key initiatives include mechanized farming and irrigation systems, with significant focus on the decades-old Middle Ogun Irrigation Project in Iseyin, Oyo State.

Joseph Utsve, Minister of Water Resources and Sanitation, stated that the project—now nearing completion—would provide 8,000 direct jobs and bolster food production through solar and grid-powered irrigation systems.

Additionally, the government has launched a $134 million partnership with the African Development Bank to enhance seed and grain production. Ministers Abubakar Kyari and Aliyu Abdullahi have also promised targeted irrigation programs to aid dry-season farming, emphasizing the urgency of food security amid soaring inflation and a food production emergency.

Despite these pledges, farmers remain skeptical. Kaduna farmer La’ah Dauda criticized the programs for being selective and inaccessible to small-scale farmers. “They create awareness only in favored areas. How will you attract new farmers if others are excluded?” he asked.

Irrigation farming, farmers argue, is still prohibitively expensive. Ifraimu Dauda, Chairman of the All Farmers Association of Nigeria (FCT), urged greater investment in affordable irrigation infrastructure, noting reliance on neighboring states for water access.

Tobi Awolope, an agriculture expert from Abeokuta, warned that dependence on rainfed farming exacerbates food insecurity, particularly with climate-induced droughts. She called for government-backed irrigation infrastructure to enable year-round crop production and stable food prices, stressing that small-scale farmers cannot afford these systems independently.

Associate Professor Unekwuojo Onuche from the University of Africa, Bayelsa, highlighted delays in government irrigation support, which he says demoralize farmers and hinder productivity. He warned that unmet promises could worsen food insecurity, increase malnutrition, and trigger social unrest.

Economic indicators underscore the urgency of the crisis. A Cadre Harmonisé report predicts that 133.1 million Nigerians could face a hunger crisis by 2025, while food inflation surged to 38.12% in October 2024, up from 26.33% in 2023, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Awolope emphasized the need for timely, inclusive interventions, warning against food hoarding and inefficiencies that inflate prices and limit access. “Farmers cannot do this alone,” she said. “The government must step in to ensure year-round food production and stable prices for all Nigerians.”

With millions at risk of hunger, experts stress that immediate action is critical to securing Nigeria’s agricultural future and averting a deepening food crisis.